State may be drenched, but ‘drought’ label remains on Valley and it’s partly about money

BY MARC BENJAMIN AND ROBERT RODRIGUEZ

The rest of California is done with the drought, but not Fresno, Kings, Tulare and Tuolumne counties, Gov. Jerry Brown decided Friday. The reason is as much about money as it is about water.

Keeping those four counties under a drought declaration ensures money continues to flow for emergency drinking water projects to help water-short communities address dry or contaminated wells, the governor’s order said.

“It’s really a tool for these communities that have a water shortage so they can get technical and financial assistance,” said Max Gomberg, director of climate and conservation for the State Water Resources Control Board. “There are still communities where the impacts from the drought are still being felt and we want to continue to provide state assistance to them.”

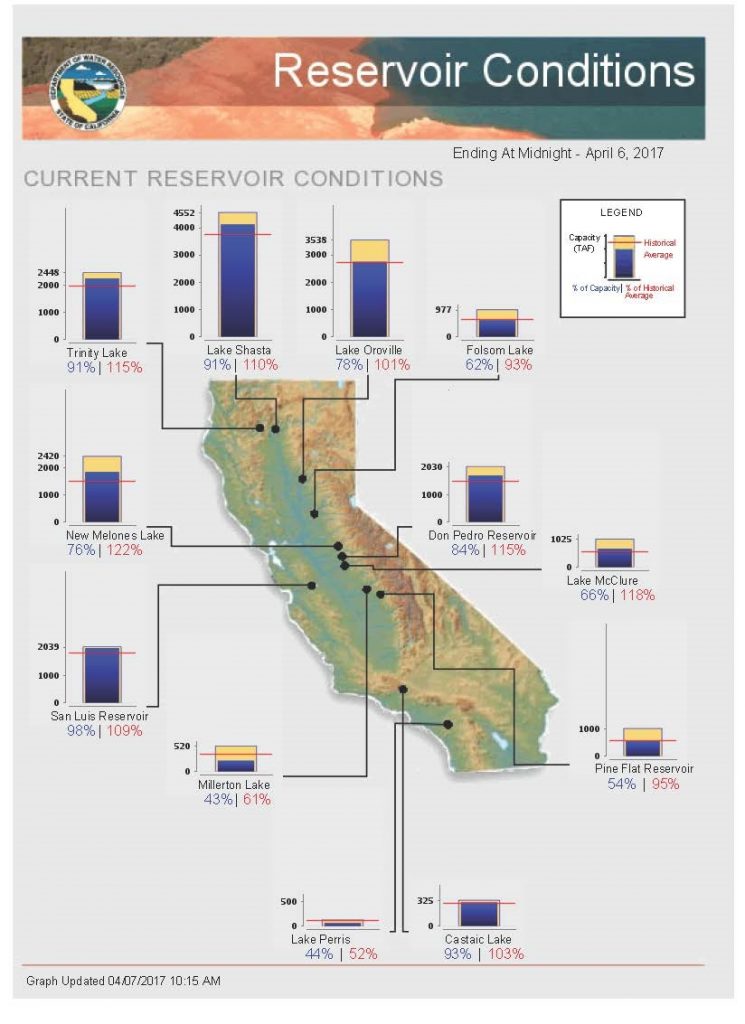

The severely dry conditions started in the winter of 2011-2012. The governor’s order said most of the conditions that prompted his drought declarations of 2014 and 2015 have diminished. Indeed, another storm was moving through California as the governor issued his order.

“This drought emergency is over, but the next drought could be around the corner,” the governor said. “Conservation must become a way of life.”

Within the four counties, most communities and farmers are not affected by the continued drought declaration, but small communities where wells have gone dry or there is no access to clean water are included, said water board officials.

It’s not a punitive measure, Gomberg said.

The extended drought declaration will allow small county communities to continue to have access to bottled water and funding for potential long-term solutions, he said.

For example, Gomberg said, “It allows us to continue the emergency measures, such as for bottled water or emergency hookups in East Porterville.”

The State Water Resources Control Board announced Friday that it has approved up to $35 million in grants and loan forgiveness to connect East Porterville residents dealing with dry and contaminated wells to clean and reliable drinking water from the city of Porterville’s public water system. State and local agencies are connecting approximately 1,100 eligible properties to the city, with the cost of the connections being paid for by the state.

Keeping the drought declaration intact also speeds up the contracting process and keeps anti-gouging provisions in effect, Gomberg said.

Besides East Porterville, other affected Tulare County communities are Monson, Seville and East Orosi. Also affected are Cantua Creek, El Porvenir and Orange Center/Daleville in Fresno County, and Kettleman City and Hardwick in Kings County.

Others affected are individual homeowners with private dry wells, said Ken Austin, Fresno County’s emergency manager.

“The state probably wanted to keep that in place until they can move those folks toward a permanent solution,” Austin said.

Cities with ample water supplies will continue to live by state rules as other communities in California’s 54 other counties, state water officials said.

“Monthly reporting is still mandated for the amount of water they are saving or not,” said George Kostyrko, spokesman for the state water board. “We really don’t want people to get into bad habits or wasting water.”

The state water board will formalize water rules by 2021 so that state officials won’t have to make new rules or revoke rules every few months because of changing conditions, Kostyrko said.

Members of the Natural Resources Defense Council were not surprised the drought emergency remained in parts of the central San Joaquin Valley, saying farmers have severely depleted the groundwater in the region.

With little to no surface water, farmers on the west side of the Valley have been heavily pumping groundwater to keep their trees, vines and row crops alive.

But the heavy pumping and new, deeper wells took a toll on groundwater supplies.

“Water may appear to be in abundance right now. But even after this unusually wet season, there won’t be enough water to satisfy all the demands of agriculture, business and cities, without draining our rivers and groundwater basins below sustainable levels,” said Kate Poole, director of the NRDC’s water and wildlife project. “So we still need to use every drop wisely. Being better stewards of our natural supplies is critical to securing a sustainable water future for California’s people, economy, and environment.”

But a spokeswoman for Westlands Water District, the largest agriculture water district in the nation, said farmers had little choice but to pump water from the ground. The district supplies water to farmers in Fresno and Kings counties as part of the Central Valley Project, a joint agreement between the federal government and the state. The water comes through the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, an environmentally sensitive area.

In the last three years, the district’s farmers have received little to no water from the Central Valley Project.

“The reason they had to pump is because they didn’t have any water deliveries,” said Gayle Holman, spokeswoman for the Westlands Water District. “Water that typically has gone to the region has stayed in the delta for the protection of fish species.”

Holman said the continued drought emergency won’t have an impact on Westlands farmers this year. They received a 65 percent allocation and are moving forward with their plans.