4 Things You Should Know About California’s Biggest Reservoir

By Craig Miller JUNE 13, 2017

It’s Probably Not the One You’re Thinking Of

Nope, not Shasta Lake. That’s California’s largest surface reservoir, which is currently bulging with more than 4 million acre-feet of water (Californians use about 40 million acre-feet in a year).

You’re not likely to find the biggest “reservoir” on a map—but you might be standing on it. It’s underground, in the vast aquifers that lie beneath sections of the state, the Central Valley in particular.

“I don’t think anybody’s tried to calculate the complete volume,” says Claudia Faunt, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in San Diego.

But we know it’s big.

‘It’s huge. But that doesn’t mean that we can extract everything that’s down there.’Thomas Harter, UC Davis

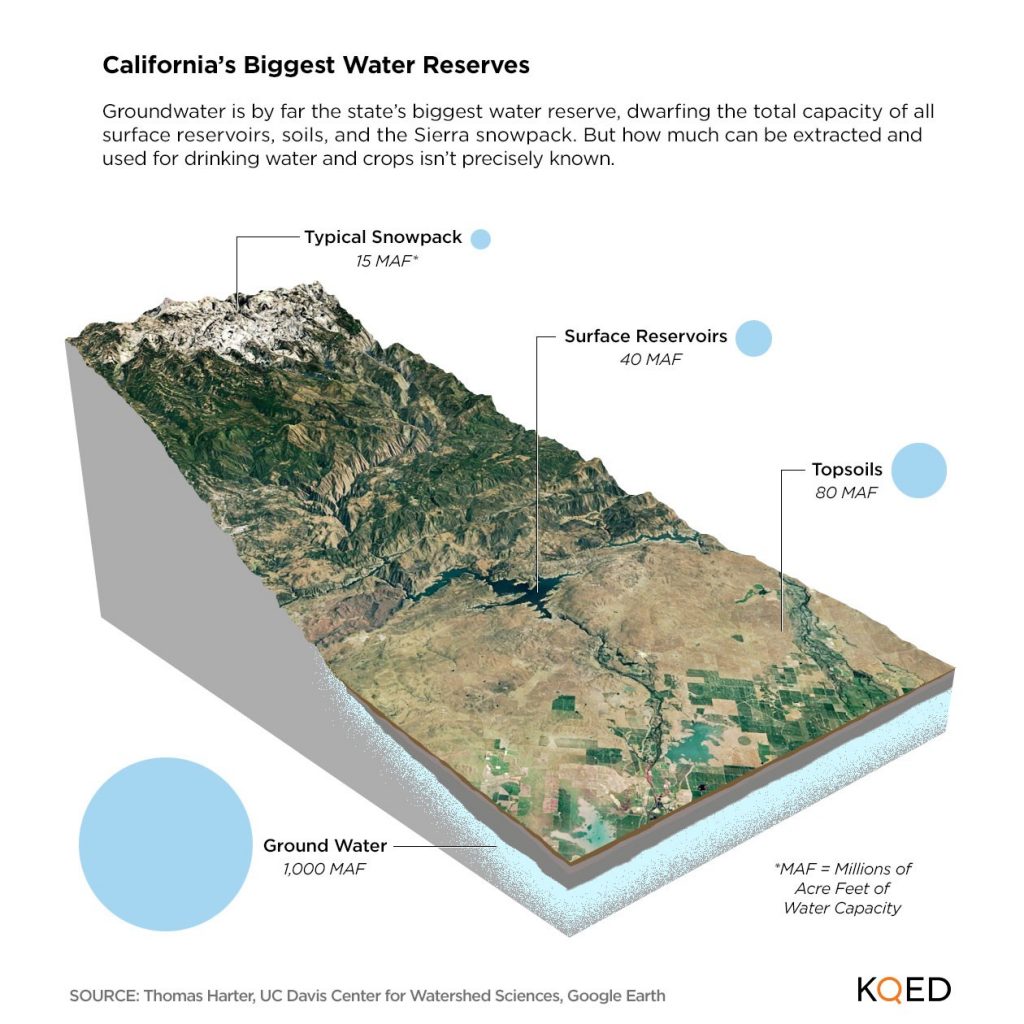

People sometimes refer to the Sierra snowpack as the state’s largest reservoir. Even though it supplies about a third of the water that Californians use annually, it’s a “drop in the bucket” compared to the state’s mother lode of groundwater. If you imagine a single bucket of water representing all the water contained in Sierra snowpack in a typical year (granted, this year is hardly typical), you would need 60-to-70 buckets to visualize all the water beneath our feet, contained in various groundwater basins.

It’s Big, But There’s a Catch

“It’s huge,” says Thomas Harter, a hydrologist and groundwater specialist at UC Davis. “But that doesn’t mean that we can extract everything that’s down there.”

Nor would that be an especially fruitful exercise, since much of the water that’s down there is not fit for drinking or even irrigation of crops in some cases. And the deeper the aquifer, the more expensive it is to pump it—hundreds or even thousands of feet—to the surface.

“Part of it is so deep that it just gets more and more expensive to extract the water,” says Faunt.

It’s in Trouble

A team of researchers at UCLA recently estimated that during the recent five-year drought, groundwater was pumped out of the Central Valley at twice the rate of the previous drought (2007-09), eventually taking out enough to fill Lake Mead, the nation’s largest man-made reservoir.

But even in “normal” years, scientists say many farmers and water agencies around the state have been pumping groundwater at an unsustainable rate.

“Basically we’re taxing the system beyond what it can take,” warns Faunt. “We’ve been using water at a rate much higher than water’s being recharged to these areas, so you’ve got a loss of storage.”

Over the course of the drought, at least 3,500 wells went dry and Harter reckons that most of those remain dry, despite the record-setting precipitation over the winter. According to state regulators, there are still communities receiving emergency supplies of bottled water after local wells dried up.

It’s Not a Lost Cause

Scientists and water planners think the state’s aquifers can be made sustainable, but it will take time and commitment.

New strategies are taking hold to recharge groundwater basins. Since we reported on one of the earliest pilot projects in 2013, farm recharge programs have gained substantial momentum, flooding fields with some of the high river flows in years like this, and using those fields as recharge basins, allowing the water to sink in and replenish aquifers below. In Orange County, water managers recycle urban water to recharge local aquifers.

In 2014, state legislators passed the landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which will, for the first time, require users of groundwater to track and report how much they’re using, and devise plans to do so in a way that doesn’t further deplete supplies. Prior to SGMA, it was essentially open season on groundwater.

As NASA scientist Jay Famiglietti has put it, “It’s not unlike your having several straws in a glass and everyone drinking at the same time and no one really watching the level.”

The first management plans are due in 2020, and full implementation of the law — which could ultimately place some restrictions on pumping — won’t happen for another decade at least.

But as the law’s sponsor, Sen. Lois Wolk (D-Davis) told Water Deeply, “When you’re digging yourself into a hole, the first solution is to stop digging.”